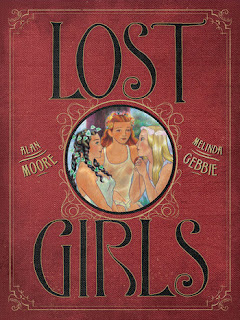

It’s been several years since I first read Alan Moore and Melinda Gebbie’s porn cum art comic Lost Girls. A potentially scandalous work, I overcame my wariness over its controversy with a trust that reflected, at the time, my relative alignment with the popular assessment of Moore’s work. Since then, however, I find myself more of a dissenting voice, questioning not the intelligence and knowledge Moore clearly brings to his writing but his often-overwrought craft in service of a muddled vision that brooks no criticism. Erudition should be an invitation to share a journey of discovery, not a wall that demands people prove themselves worthy to enter the ivory tower – a distinction Moore’s work seems to have increasingly abandoned.

Fundamentally, the problem I see in his work is a common one among writers; the tendency to thrust more ideas into a story than is necessary and meaningful. For Watchmen, it’s Moore’s inclusion of the god-like Dr. Manhattan that undermines an otherwise nuanced critique of the era’s prevailing mood of superhero worship and a study of the morality of power via the mythologize of costumed vigilantes. As a self-proclaimed puppet able to see the cosmic strings, Dr. Manhattan serves to establish a strictly deterministic universe in which all actions are predetermined and free will, along with the moral accountability that comes with it, is an illusion. Whatever critique of superheroes Watchmen can offer is, on its own terms, impossible given the characters’ lack of agency. After all, what morality can wind-up toys have? The layering of a free will vs determinism debate is too much for the story to bear, especially when Dr. Manhattan is the only character to grapple with it.

But Watchmen is a model of lean storytelling compared to the League of Extraordinary Gentlemen books, orgies of literary references, tangents, pureed concepts, metafictional wankery, pastiche fetishes, and an unpleasant penchant for the lurid that arrive nowhere if the standard involves meaningful characterizations and relatable narratives. The Illuminatus! Trilogy by Robert Shea and Robert Anton Wilson, which predates League by about 25 years, remains to me the quintessential model of how to tell philosophically provocative and meaningful, yet entirely gonzo, post-modern meta-stories. League, while admirable and often clever in both ambition and grasp of literature, comes across as posturing in comparison.

These excesses stand out to me precisely because of those works in which Moore does display the focused storytelling of a masterful writer with keen insights to offer in his characters, plots, and narrative themes. The first is V for Vendetta; a suspenseful and satisfying political thriller infused with a deliciously provocative ideological perspective. Words and images complement each other beautifully to deliver an outstanding example of what comic book storytelling can be. The other is From Hell, Moore’s provocative metaphysical meditation on the horrors of the 20th century as ritually presaged by Jack the Ripper’s murders.

So what of Lost Girls, Moore and wife Gebbie’s ambitious attempt to bring together art and pornography into something that could, in the mating, transcend both? The book is premised on a chance encounter between three characters extracted from classic children’s literature – Alice, Wendy, and Dorothy – at the posh Austrian hotel Himmelblau shortly before the onset of World War I. The narrative hasn’t even begun to undress when, alas, Moore’s tendency for excess shows itself. It happens in a conversation between two inconsequential servants who, in Moore’s process of hinting at Alice’s libertinous character, reference an unseen black character using the “N” word. The word is not only jarring, but entirely gratuitous since the book doesn’t deal with racial issues and is populated entirely by white characters. The first question that comes to mind is: do we really need a scruffy old white guy carelessly and pointlessly bandying racially charged words just to prove whatever notion of authenticity he harbors for his work – in a narrative fantasy? Next is: should we start questioning why Moore is so fixated on English and American literature, with nary a look outside of white borders?

Moving on to the broader thematic excesses, Moore’s decision to reference World War I is hard to reconcile with the overall erotic goals of his fantasia. Other than some passing references, particularly through the transient character of a convalescing soldier, Captain Rolf Bauer, the specter of war only haunts the narrative when readers remember it. Until the end, that is, when it seems as if Moore suddenly remembers what time period he set his story in, at which point the most he can muster are banal musings on how much better it would be for the young men to be home having sex rather than fighting/dying, along with a final sequence of panels depicting an eviscerated soldier on the battle field. When the post-orgasmic glow of an erotic story comes from artillery shells rather than sex, something’s gone awry with the storytelling.

While to my eyes Moore has a tendency for overworking his sentences to the point of making H.P. Lovecraft look like Hemingway by comparison, even when he’s consciously aping classic authors, Lost Girls suffers more from his need to provide a running commentary, dialogue, or some kind of verbiage on every panel instead of trusting Gebbie’s artwork to excite readers. The lack of balance between words and images is particularly unfortunate in the story’s flashbacks, patterned in the broadest sense from Alice in Wonderland, Peter Pan, and The Wizard of Oz. Because Moore has Alice, Wendy, and Dorothy narrate their life stories, essentially explaining what Gebbie illustrates, most of the book’s characters don’t benefit from a voice, and therefore personality, of their own. Moore essentially locks us into the women’s interpretation of events through their narration, instead of allowing dialogue and images to guide readers to their own understanding of the pivotal moments in the lost girls’ lives. There’s so much writing that one wonder why Moore bothered with a graphic novel format for the story he wants to tell. The book’s limp drama is all the worse given that, for all the writing, Moore fails to create relationships that evolve throughout the course of the story. A notable example is between Wendy and her husband, the condescending and chauvinistic Harold Potter with whom marital bliss is tragically lacking. One would hope that with Wendy’s sexual escapades and Harold’s eventual indulgence of his repressed homosexual urges, each character might learn something to lead to some kind of change in themselves and their relationship to each other. But no. Harold remains every bit the condescending paternalist by the time he drives out of the plot; he and Wendy never even have a conversation to reflect on the meaning of their experiences. The lost girls themselves are similarly deprived of any depth of relationship to each other, since Moore requires very little to get them fucking each other and sharing their life stories. Whatever healing they arguably gain from recounting their trauma-laced sexual comings of age doesn’t lead to anything. For a book with literary aspirations, Lost Girls is curiously dry when it comes to character development. Like a burlesque dancer who comes on stage without any clothes on, and thus no means to tease and tantalize the audience, there is no buildup and release in Moore’ storytelling.

While the above shortcomings provide more than enough interruptus for the book’s coitus, it’s the depiction of child and teenaged sexuality that looms largest over the entire project. The controversy is arguably exaggerated, partly because Moore and Gebbie are not the first, nor the most boundary-pushing, artists to engage the topic, but also because in a book’s storytelling isn’t in service of gratuitous titillation. While there’s no accounting for how readers will personally react, the most questionable panels are generally a minority in a book that is, essentially, cover to cover sex mostly between adult characters. And violence, while implied in a few rare instances, is never depicted. So what, exactly, are Moore and Gebbie doing? The youth sexuality is presented in two ways. First is methodological, in that the story concerns three women’s life stories from the perspective of their sexuality, which means consistent explicitness for them as both youths and adults. There is context, biography, and characterization to what Moore and Gebbie offer, regardless of my view that it ultimately doesn’t amount to very much. Second are the short story pastiches, presented as excerpts from a scandalous little white book the hotel owner makes available to every guest in their rooms. A few of these pastiches consist of big, happy, incestuous, all-age family orgies that are so ridiculous and over-the-top, the impression is neither serious nor erotic but, intentionally or not, hilarious.

From here we get to the point of the book, the climax of its project that serves to pre-emptively defend their choice of methodology and subject matter from criticism. Through the character of Mr. Rougeur, the Hotel Himmelblau’s owner and the coy author of that little white book, Moore makes his argument during the grand orgy that caps off the story:

“You see? Incest, c’est vrai, it is a crime. But this? This is the idea of incest, no? And then these children: how outrageous! How old can they be? Eleven? Twelve? It is quite monstrous … except that they are fictions, as old as the page they appear upon, no less, no more. Fiction and fact: only madmen and magistrates cannot discriminate between them.”

To underscore the point, the not-entirely-reliable Mr. Rougeur says this right before observing that he is having sex with a thirteen-year-old. And thus, Moore believes, the trap is set: what, exactly, is there for readers to be morally outraged about? There is no reality, no action, no person to point to. Nothing, indeed, is actually happening, except as a mental fiction, an interpretation of words and images on the page.

But the trap is far from shut, not the least because Moore isn’t offering a new argument. Horror creators have long pointed to the fictional nature of their work as a moral bypass for the extreme violence and suffering they depict. And as long as there have been artists, there’s been a struggle over what constitute acceptable artistic subjects – with sexuality, of course, being a common flashpoint of censorship efforts. While there will always be debates in this area given a pluralistic society, particularly over where the boundaries of tolerance are drawn, the notion of freely exploring ideas even in light of their relative ability to offend is for the most part accepted and settled in liberal environments. Besides, what is pornography or it’s more refined sibling, erotica, if not the exploration of fantasies both attainable and unrealistic? It simply isn’t clear with whom Moore is arguing with.

Moore presenting an old argument to an outdated problem is unfortunate enough, but all the more so because it means he misses the opportunity for more interesting and relevant questions. The issue, really, shouldn’t be what responsibility reality has toward art, but what responsibility art has toward reality. It’s a matter of psychology and the role of fantasy in our mental health. While I wouldn’t argue that fantasy is necessarily bad, Moore’s declaration of support for an amoral mental playground neglects how thoughts influence our emotional states and patterns of behavior. Pornography, like reality TV, can warp our understanding of reality and can, without a skillful mindset, lead to harmful consequences in terms of body image, performance expectations, relationships, and related expressions of sexuality. When combined with mainstream cinema’s tendency to associate sex with menace (i.e. in thrillers and horror) or embarrassment (i.e. in sex comedies), our cultural understanding of sexuality tends to be more debilitating than liberating. Rephrasing the question, then: how can the art of sex help us enjoy our sexuality with skill and empathy in our day-to-day reality? Unfortunately, Moore doesn’t even offer a rationale or exploration for his declaration via Mr. Rougeur, so Lost Girls is certainly not positioned to explore any other questions.

Whether, despite all that, Lost Girls is of the one-handed or two-handed persuasion isn’t for me to say. It’s different strokes for different folks, and there’s enough variety for at least some panels to achieve some kind of effect. That said, I found the book to be singularly lacking in joy. The WWI context contributes to the downbeat impression, but really it’s Moore’s decision to retell whimsical stories as personal traumas that makes the book more cold shower than hot fling. For Alice, the journey to Wonderland beings with a sexual assault by a family friend, and continues with her upbringing in an all-girls boarding school from which she falls in with a lesbian dominatrix, becomes addicted to opium, and is subjected to all manner of sexual debaucheries and twisted power games. Wendy’s experience involves her encounters with Peter Pan, over which looms the threat of a sexual predator nicknamed the Captain, a plot whose resolution leaves Peter a prostitute and Wendy sexually repressed. Of the three, only Dorothy has a less brutal retelling, in that after discovering herself during a tornado she merrily fucks her way through farmhands inspired by the Cowardly Lion, Scarecrow, and Tin Man, before moving on her father the Wizard. Other than a devastated stepmother, Dorothy is the only lost girl to emerge relatively unscarred from her teenaged experiences.

Not only is this grim stuff, glibly exploited, Moore’s decision also undermines the sexual freethinking he claims to support by resorting to unfortunate cliches, from Harold Potter’s latent homosexuality expressed as male chauvinism to Alice’s maturation into lesbian as reaction to a man’s sexual assault, immersion in an all-female environment, and drug-induced mental flights of fancy. He and Gebbie don’t get caught up in obsessions over body types and sizing, but that was the least they could do. And just as Lost Girls disappoint in terms of LGBTQIA+ allyship, it does nothing to alleviate the concerns raised by Moore’s questionable record in handling instances of sexual violence, from The Killing Joke to the Invisible Man’s crimes and punishment in League of Extraordinary Gentlemen.

Furthermore, Moore’s retelling of Carrol, Baum, and Barrie’s stories amounts to an act of artistic bad faith given his habit of complaining about people using his characters in follow-up works, such as the Watchmen prequels and sequel, while having made a career appropriating other artist’s characters for his own purposes. (Watchmen repurposed old Charlton Comics characters in the form of substitutes. Neonomicon and Providence directly H.P. Lovecraft’s stories. League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, of course, steals from everyone.) The outcome is a book that doesn’t engage with the original works, but appropriates and replaces them with little opportunity to deepen one’s interpretation of both. By comparison, look at how American McGee’s Alice games engage with Carroll’s books as a dialogue. Interpreting the books’ Wonderland as Alice’s healthy, childhood mental landscape, the games act as sequels exploring what happens when personal and social trauma warp Wonderland’s whimsy into gothic horror with Dickensian overtones.

Having read Lost Girls three times, with diminishing returns, the fact that there is much to write about isn’t a measure of how rich but rather how disappointing the book is. With that, the final word belongs, actually, not to Moore’s writing but Gebbie’s illustrations. Though a bit static and low-energy, her storybook style is nevertheless beautiful and inviting, explicit but not anatomically obsessive. I’m not the first to point out the cleverness she often displays in her panels, such as the sequence in which shadows frolic to emphasize the actual frigidity of Wendy and Harold Potter’s marriage. Also admirable is her ability to change her style to suit the various pastiches splashed throughout the narrative. While I don’t think her art is enough to compensate for Moore’s writing and storytelling – a comic’s success rests, as I mentioned, on the balance of words and images – that’s where the book blossoms best, when it blossoms at all. And with that, I’m perfectly fine with saying that I’ve reached the end of the daisy chain when it comes to Moore’s work. If nothing else, Lost Girls motivates to discover other artistic voices.

No comments:

Post a Comment